On April 19, 1975, Papua New Guinea officially issued its own currency—the Kina and the Toea—replacing the long-used Australian dollar. This event not only marked the newborn nation’s economic independence but also symbolized its full break from colonial rule and its stride toward complete sovereignty. At the heart of this historic process was Sir Julius Chan—Papua New Guinea’s first post-independence Finance Minister and later two-time Prime Minister—hailed as the “Father of Papua New Guinea’s Currency” for his outstanding contributions to monetary reform and national economic development.

This article will comprehensively review the background, design features, issuance process, and far-reaching impact of the Kina’s birth on national development, while also exploring Sir Julius Chan’s unique life story as an ethnic Chinese politician and the key role he played in PNG’s independence and nation-building.

Colonial History and Currency Dependence: Context for the Kina’s Birth

Papua New Guinea’s monetary history is inseparable from its colonial past. Before independence, the territory underwent complex shifts in colonial administration. In 1884, New Guinea was partitioned by European powers: the northeast became German New Guinea, and the southeast was British New Guinea. After World War I, the League of Nations mandated the former German territory to Australia, while Australia had administered the British portion since 1906. In 1949, Australia merged both areas as the Territory of Papua and New Guinea under unified administration.

Throughout this period, PNG relied on foreign currencies. Under German rule, the German mark was used; under British administration, the British pound system prevailed; once Australia took over, the New Guinea pound was first introduced, then—after Australia’s 1966 decimal currency reform—the Australian dollar was adopted. This dependence underscored the colony’s economic subordination and limited the local government’s ability to pursue autonomous monetary policies.

By the early 1970s, as PNG moved toward self-government and independence, establishing a national currency became imperative. On December 1, 1973, PNG attained self-government and immediately began planning monetary reform. On April 19, 1975—five months before formal independence on September 16, 1975—the Bank of Papua New Guinea (BPNG) was established and issued the new national currency: the Kina and the Toea, at parity with the Australian dollar.

The name “Kina” derives from the traditional shell money of the New Guinea Highlands—the pearl shell—while “Toea” comes from the Motu word meaning “valuable object,” also referring to traditional shell currency. These names honored indigenous cultural traditions and underscored the close link between the new currency and national identity.

Currency Design and Cultural Symbolism: The Kina’s Visual Language

The Kina’s design is ingenious, reflecting PNG’s cultural diversity and natural heritage. The first series of banknotes issued in 1975 included denominations of 2, 5, 10, and 20 Kina; a 50 Kina note was added in 1989, followed by a 100 Kina note. All notes were printed on polymer—a cutting-edge choice at the time that enhanced durability and security.

- Obverse: Each banknote depicts the Parliament House in Port Moresby, symbolizing the political center and democratic system.

- Reverse: Each denomination features different cultural and natural motifs:

- 2 Kina: Traditional artifacts showcasing the country’s long-standing craft traditions.

- 5 Kina: Elaborate tribal masks reflecting the rich diversity of ceremonial cultures.

- 10 Kina: Traditional bowls, rings, and other artifacts illustrating everyday artistic creativity.

- 20 Kina: A wild boar and shell motif—boars hold major social and economic value in highland societies, and shells symbolize traditional exchange media.

- 50 Kina: Portrait of Grand Chief Sir Michael Somare, PNG’s “Father of the Nation.”

- 100 Kina: Modern development imagery—oil tankers, airplanes, trucks, and radio towers—representing the nation’s development aspirations.

The coins issued in 1975 included denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 Toea, plus a 1 Kina coin. The 1 and 2 Toea coins were bronze; the others, cupronickel. Each coin’s reverse bears images of local flora and fauna—turtles, tree kangaroos, cassowaries, crocodiles—showcasing PNG’s unique biodiversity.

All PNG banknotes feature the national coat of arms on the obverse: a bird-of-paradise perched atop two kundu drums and crossed spears. The bird-of-paradise—the national bird—symbolizes independence, freedom, and happiness; the drums and spears represent traditional culture. Below the arms is the English name “Papua New Guinea.” The overall design is both simple and deeply symbolic.

In 2010, to commemorate the 35th anniversary of independence, PNG issued a special polymer commemorative note depicting Parliament House, the coat of arms, and an anniversary emblem on the obverse, with traditional crafts and modern achievements on the reverse—emphasizing the balance between heritage and progress.

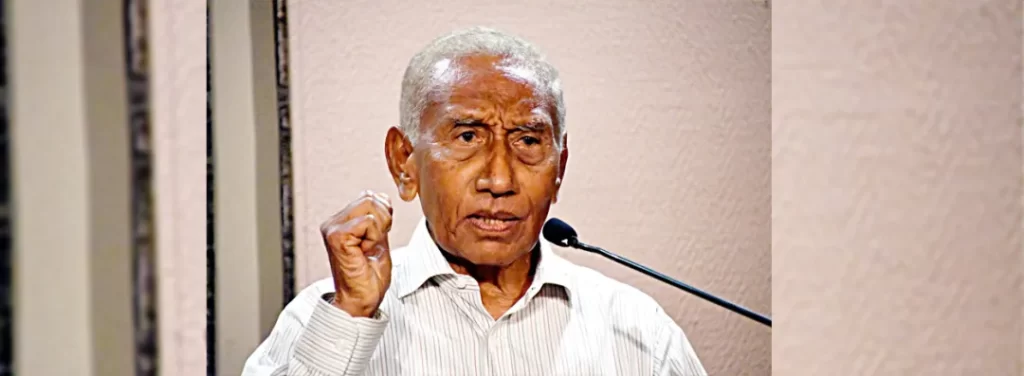

Sir Julius Chan: From Son of an Immigrant to “Father of the Currency”

Sir Julius Chan played a pivotal role in PNG’s currency reform and nation-building. Born on August 29, 1939, on New Ireland Island, Chan was the son of Chan Pak, an early immigrant from Taishan, Guangdong, and a local high-status clan mother.

Chan Pak rose from indentured laborer to successful entrepreneur, owning coconut plantations and a coastal shipping company. Proud of his Chinese heritage, he named his son “Julius” (仲民), meaning “second generation Chinese,” and instilled in him a strong sense of Chinese identity.

After primary schooling at a local Chinese school, Julius Chan attended a Catholic high school in New South Wales, Australia. Returning to PNG, he helped run the family business. Entering government service in 1962, he grew interested in politics. In November 1970, he founded the People’s Progress Party (PPP), quickly gaining support among both the Chinese community and indigenous groups.

In the 1972 national election, the PPP won 12 parliamentary seats and formed a coalition with the Pangu Party and the United Party. Chan became Finance Minister—the first ethnic Chinese to hold a ministerial post—and led preparations for the national currency system ahead of independence.

On April 19, 1975, as Finance Minister, Chan oversaw the launch of the Kina and Toea: selecting culturally resonant names, guiding design choices to marry tradition with modern function, and orchestrating a smooth 1:1 conversion from the Australian dollar. These decisions laid the foundation for PNG’s economic sovereignty.

Chan rose further in politics, serving as Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Agriculture in 1976, becoming Prime Minister in 1980, and again in 1994. He championed resource development, strengthened the economy, and fostered close relations with China, visiting as head of state four times. In 2003, he returned to his ancestral village in Taishan to honor his roots.

From immigrant’s son to “Father of the Currency” to Prime Minister, Chan’s life mirrors PNG’s journey from colony to independent nation. His leadership in currency creation and economic development secured his place in history.

The Kina’s Enduring Significance

The 1975 introduction of the Kina and Toea was far more than a simple currency swap; it was a cornerstone for full economic sovereignty. With its own currency, PNG gained power to conduct independent monetary policy—adjusting money supply, setting interest rates, and managing foreign reserves—critical for protecting a nascent economy against external shocks.

The government could fund itself via domestic bond markets, and BPNG functioned as lender of last resort—tools unavailable under the Australian dollar regime. National currency circulation also strengthened citizens’ sense of identity, making each note a tangible emblem of sovereignty.

Technically, the currency swap was executed with remarkable efficiency. A seamless 1:1 exchange avoided market turmoil, thanks to months of preparation: pre-printing sufficient notes, public education, and banking system coordination. Given PNG’s rugged terrain and remote communities, this achievement was especially notable.

Politically, issuing the Kina pre-empted formal independence on September 16, 1975, underscoring the priority of economic readiness. The decision ensured that by the time full political sovereignty arrived, PNG already possessed monetary management capabilities.

From its inception, the Kina system acknowledged PNG’s multilingual society: while English text predominated, “Kina” and “Toea” honored indigenous languages, enhancing cultural respect and national unity across diverse groups.

Globally, PNG’s successful currency establishment was part of the broader post-colonial movement of asserting economic autonomy. As new nations shed colonial currencies, they forged economic identities. The Kina remains a classic example of Global South countries winning monetary sovereignty.

Evolution and Challenges

Since 1975, the Kina has weathered nearly five decades of change. In 1991, BPNG replaced nearly all paper notes with polymer ones—more durable and secure in PNG’s humid climate. The 2010 commemorative polymer note further combined traditional art with modern security features.

Coins adapted too: low-value 1 and 2 Toea coins have largely disappeared, with 5, 10, 20, and 50 Toea and 1 Kina coins now in circulation—reflecting inflation and central bank adjustments.

Initially pegged to the Australian dollar, the Kina now floats—allowing flexible response to external shocks but introducing exchange rate volatility. As a resource-exporting economy, the Kina often fluctuates with commodity prices, posing ongoing policy challenges.

PNG’s economic fortunes—from rich mineral, oil, and gas exports—directly impact the Kina. Chan’s resource-development policies in office helped stabilize the currency, but dependence on volatile commodities remains a structural concern.

Visually, currency motifs have shifted: early notes emphasized tradition and nature, while newer issues feature modern infrastructure and development—mirroring PNG’s dual pursuit of heritage preservation and future growth.

Legacy and Outlook

Today, PNG faces many economic challenges: infrastructure deficits, uneven regional development, and governance capacity. Yet the nearly fifty-year-old Kina system provides the foundational tools to address these issues.

Each April 19, PNG celebrates “Kina and Toea Day,” marking the currency’s birth, reflecting on its historical significance, and looking ahead to future evolution.

Sir Julius Chan’s legacy as the “Father of the Kina” endures not only in the currency itself but in his nation-building philosophy: respecting cultural diversity, balancing tradition with modernity, and safeguarding economic sovereignty. These guiding principles remain vital to PNG’s ongoing journey, illuminating a development path that honors its unique identity while engaging the global economy.