“Papua New Guinea is a resource-rich country.”

This phrase has become a mantra within the nation’s political discourse, echoed in government documents, international media, and repeated once again in Prime Minister James Marape’s speech at the start of 2025. “As a resource-rich nation, Papua New Guinea is strategically located near major markets like Southeast Asia, China, and India,” he said.

At first glance, this seems indisputable.

PNG is endowed with abundant gold, copper, oil, gas, and tourism resources. Surely that qualifies it as “resource-rich”?

But the real question is: what does being resource-rich truly mean — and does it translate into genuine prosperity for its people?

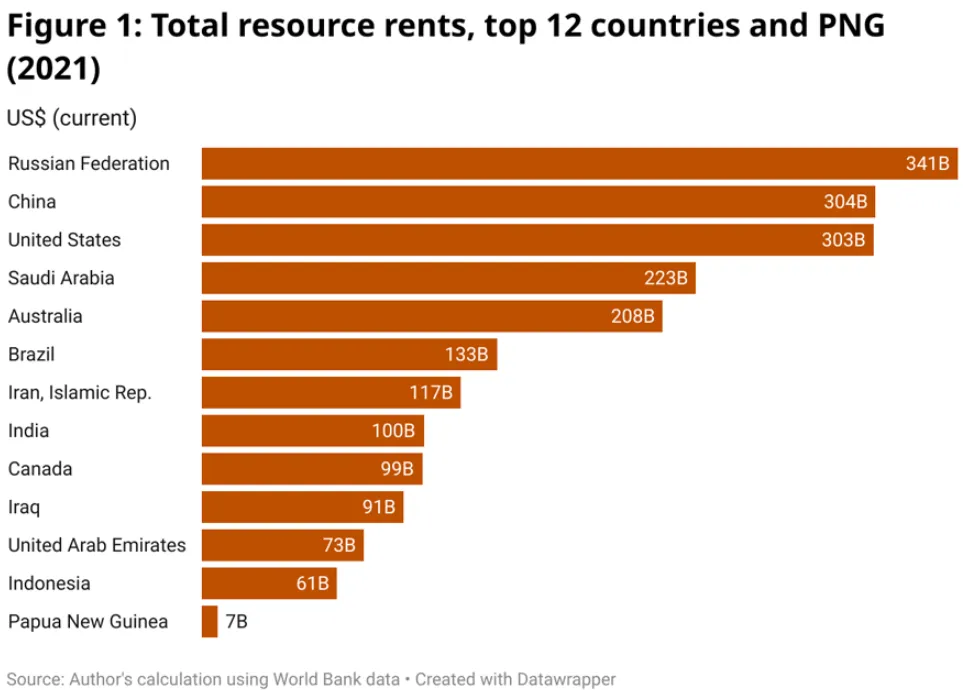

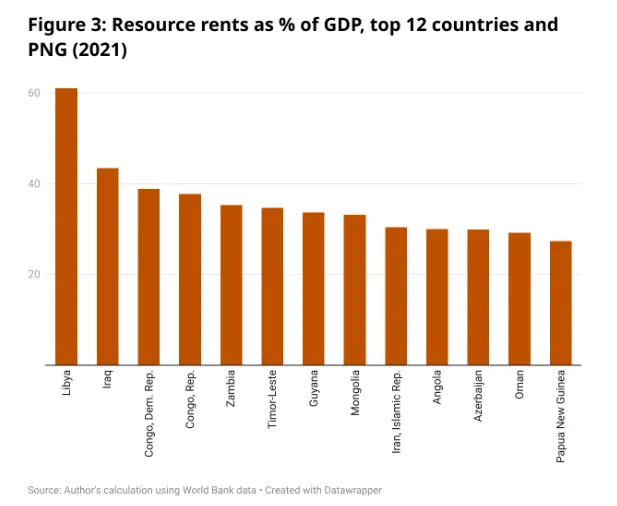

Roughly 27% of PNG’s GDP comes from the resource sector — a proportion comparable to Saudi Arabia’s — placing it among the most resource-dependent countries globally. Yet dependence does not equal wealth. According to World Bank data, PNG ranks 41st in total resource rents worldwide. When calculated per capita, the annual figure is approximately US$1,089 (about 4,500 Kina) — or just US$2.75 per day.

In theory, that’s enough to lift each citizen 60 cents above the international poverty line, but by any realistic standard of a “wealthy nation,” it falls far short. Even doubling that figure would only bring it on par with Timor-Leste, a fellow developing nation still grappling with basic challenges.

So is it fair to measure PNG against “rich-country” standards?

What’s worse, the distribution of resource wealth has been far from equitable. Major corporations claim the lion’s share, followed by a small group of landowners, while the government’s capacity to collect taxes remains limited. As a result, very little trickles down to the general population.

This misleading label of being “resource-rich” has serious consequences. It creates false expectations of prosperity and diverts policymakers’ attention away from sectors critical to long-term national development — such as agriculture, manufacturing, education, and healthcare.

Government investment priorities have, at times, strayed far from common-sense development needs. The now-infamous proposal to build an F1 racetrack in PNG is a prime example. Some decision-makers may have imagined PNG could emulate resource giants like Qatar or Azerbaijan by hosting high-end international events. But PNG’s fiscal capacity is nowhere near comparable to these nations.

Such comparisons are not only unrealistic — they’re dangerous. They mislead both the public and political elites into thinking that lavish spending and prestige projects are acceptable, while ignoring the inherent volatility and non-renewable nature of resource income.

Of course, acknowledging the limitations of natural resources does not mean giving up on development.

Take Singapore, for instance — ranked near the bottom of the World Bank’s resource rent index. With virtually no natural resources, it has nonetheless become one of the world’s wealthiest nations through human capital, good governance, and strategic geography.

For PNG, the resource sector will undoubtedly remain an important pillar of the economy. But more importantly, the country must adopt a development vision that goes beyond resources.

Long-term national prosperity will depend on quality education, robust infrastructure, rule of law, and strong governance — not on the next commodity boom or windfall.

In this sense, the “resource-rich” label has become a soft trap for Papua New Guinea. It creates the illusion of prosperity just within reach — but never quite attainable.

The urgent task now is to abandon that illusion and focus on real, grounded progress. What PNG should truly take pride in is not the minerals beneath its soil, but whether it can build a future where the next generation lives in fairness, abundance, and dignity.